About a year ago, I caused the biggest incident (a.k.a. SEV) since the formation of our team. After rolling out my changes, one of the services dropped all the data it received.

Here is what happened and what I learned from it.

Context

Our system is a pipeline of a few streaming services, i.e., the output of one service is the input to the next service in the pipeline. These services process data belonging to different categories. Due to tight timelines, our initial implementation didn’t allow for distinguishing them. While this implementation worked, monitoring, validation, and data analysis were challenging for a few teams. To make the lives of all these teams easier, I decided to implement support for categorization properly.

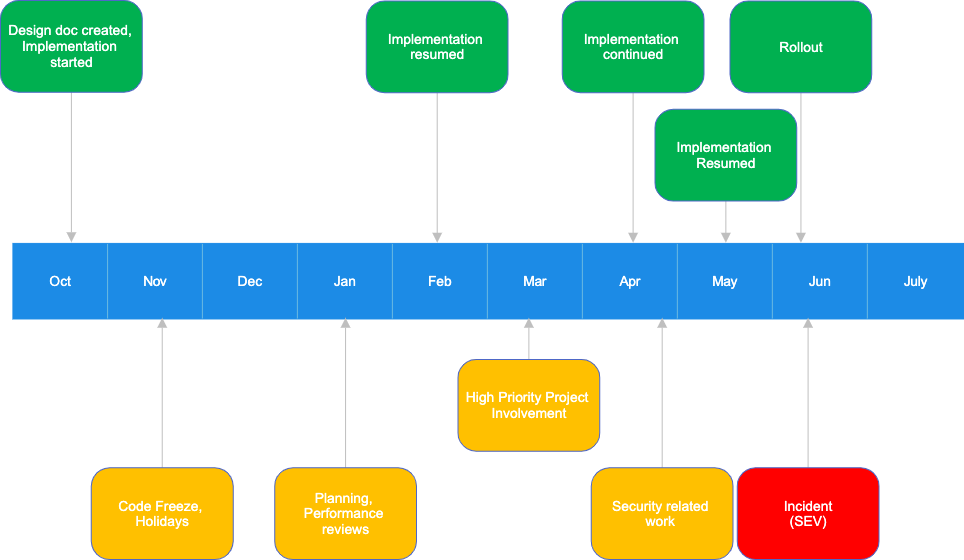

As my changes weren’t supposed to modify the output of the pipeline, I considered them to be refactoring. Even though I knew this refactoring would be massive and span a few services, I treated it like a side project. I didn’t set any timelines or expectations and worked on it in my free time. As a result, the project dragged on for months because I could only work on it intermittently. The timeline below depicts it:

After months of on-and-off work, I finished the implementation in late May and rolled out my changes in early June. A few hours later, alerts indicating missing data went off. My rollout was the primary suspect of the outage, and we quickly confirmed it was indeed the culprit.

Root cause

Our investigation found that the last service in the pipeline had a misconfigured feature flag, which caused the outage. The purpose of this feature flag was to prevent duplicate data from being emitted during validation. It was necessary because, during validation, I sent uncategorized and categorized data sets through the pipeline and compared them. However, the pipeline should only ever output one dataset, so one had to be removed. The easiest way to achieve the correct output during validation was to drop the categorized dataset. The feature flag controlled this behavior.

During the rollout, upstream services started producing only the new, categorized dataset. However, because the feature flag still used the validation setting, the downstream service dropped all data it received.

That’s the technical explanation. But the more interesting question is: why did I forget to configure the feature flag correctly?

I added the feature flag as one of the first implementation steps—almost half a year before the rollout. Because of all the distractions, I forgot that I even touched this service. During the rollout, I again focused only on validating upstream services because, in my mind, these were the only services I modified.

Lessons learned

Every incident is an opportunity to learn something. This one is no different. Here are the two most important lessons I learned from it.

Lesson 1: Avoid taking on tasks I know I can’t properly focus on. Working on and off was very ineffective. Each time I resumed working on my project, I had to spend considerable time remembering where I left off, only to pause again soon after. Instead, I should have worked with my manager to find an engineer who could work on this project without distractions, deliver it faster, and learn from it.

Lesson 2: A reminder always to validate changes end-to-end. In my case, I only focused on services I thought I modified. Had I checked the pipeline output, I would have caught the issue almost immediately.

The end-to-end validation principle applies to any software development work. One example could be unit tests: passing unit tests don’t guarantee that an application works as expected. Quickly loading the application and verifying changes can help catch issues that unit tests didn’t flag. This is important because users care whether the application works, not if unit tests pass.