This is the first post in a series that talks about my recent project dubbed “Cloud enabled Commodore 64”. The project is an attempt to connect Commodore 64 to Cloud (Azure) and let it communicate with a variety of clients – both modern and vintage. Here is a demo of the final result:

I had the idea of connecting Commodore 64 to Cloud in my head for a really long time. When I initially tried to take a stab at it, it was apparent that I didn’t have skills necessary to build the hardware. When the C64 WiFi modem came out I have already moved on and did not pay attention. Until that one, dark autumn Friday night, when I was browsing ebay and came across a C64 WiFi modem which I promptly bought. To be honest I did not even spend too much time looking at the pictures and when it arrived, I was very surprised to notice that the modem is just a NodeMCU Esp8266 board that can be plugged in to the C64 User port. This was a very pleasant surprise because I was already familiar with NodeMCU – I used it for one of the first ASP.Net Core SignalR demos.

The main purpose of the original C64 WiFi modem and its firmware was to allow Commodore 64 owners access BBS’es around the world with software called Nova Term. This did does not appeal to me at all. Due to the times and place I grew up in I did not even have access to a landline and the only way to get new software was via swapping with other enthusiast either at school or over mail. I did spend a night playing with the modem and figured one can use this modem to connect to a BBS directly from a Mac or Linux using screen (or a PC using Putty). This convinced me that the modem works and that my idea suddenly became real.

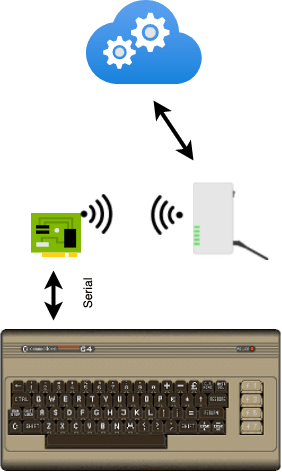

How? – High level design

The modem pretty much dictated the design. The communication between C64 and the modem would use Serial protocol and the modem would require a firmware that would deal with all network related affairs.

I decided on a few principles upfront:

- Modem firmware will only deal with network (i.e. will not include client specific logic)

- C64 software will be written in 6502 assembly

- C64 software will use built-in Serial routines (KERNAL)

- I will use Azure as the cloud provider and will use SignalR

I decided to use 6502 assembly to remember the fun I had using it on my first computer when I was a kid. Right decision or not, it made me appreciate how much progress have been made with regards to programming since then.

The KERNAL routines for Serial protocol are infamous for their bugs but they work OK at low speeds. There are several routines that patch and fix KERNAL code responsible for serial communication and allow reliable transfers at 2400 or even 9600 bauds. After I started investigating, I quickly realized that researching this subject would be interesting but also very time consuming. While it would be nice to have faster serial communication, running at 1200 bauds felt to be fast enough for this project – let’s be honest, in today’s world 9600 bauds is as fast (or as slow) as 1200 bauds and I never thought this project could have any practical usages.

Finally, I decided to go with Azure simply because I am much more familiar with Azure than AWS or Google Cloud. I am also quite familiar with SignalR and how it allows building engaging demos with the canonical example of a chat app being something that might even seem a legit use case for a 40-year-old computer.

These were my thoughts before I embarked on this project. I will however revisit some of these decision in a future post where I will reflect on surprises I encountered and what I could have done differently.

Why?

As noted before – this project was never supposed to have any practical usages. I just thought it would be a fun hobby project. And it really was. Seeing it working live on a real hardware was a blast.

That’s it for today. Next time I will go over the environment I used to develop this.