Joining a new team is intimidating. There is always much to learn – new people, new processes, and a new code base.

Ramping up on your new team’s code base is difficult, but knowing how to work effectively in it is crucial to your success. So, how do you do it quickly?

My mid- and early senior developer years were intense. Due to a mix of reorgs and personal interests, I found myself on a new team every year or so. As a result, I had to learn new codebases in quick succession. They included .NET System.Xml, OData, Entity Framework, Entity Framework Designer, ASP.Net SignalR, ASP.Net Core, and the Alexa mobile app, and most of them were over one hundred thousand lines.

The first couple of transitions were slow and overwhelming. But they helped me develop a strategy I used later to quickly get up to speed on new codebases.

Get your hands dirty ASAP

The sooner you start working actively with the code base, the sooner you will get productive. Reading documentation can be helpful, but nothing can replace the hands-on experience.

When I joined Amazon, I asked my manager to assign me a simple bug to fix on my first day. Even though the fix amounted to a single line of code, it took me a few days to send it for review. It might seem long, but this quest was not about fixing the bug. Rather, it was about forcing myself to set up my development environment, learn how to build and run the code, write unit tests, and debug our product.

Review code

Each team has its way of letting members know there is a new PR (Pull Request) for review. It could be email, chat, or review tool notifications. Whatever it is, subscribe to this channel and start reviewing PRs. You won’t understand much initially, but you may still catch some bugs (e.g., off-by-one errors). More importantly, these reviews will allow you to ask questions and gather a broader context of what the team is working on.

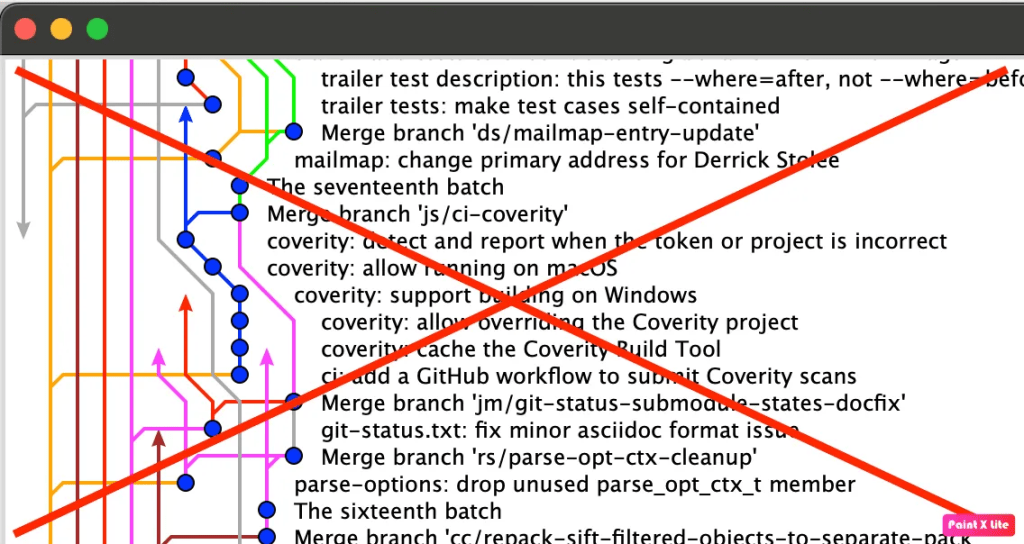

Identify code that matters

The 80/20 rule does apply to codebases. This is especially noticeable in the bigger ones, where most code changes developers make are concentrated in one area. Knowing which code it is allows you to focus your ramp-up on the area you are likely to work on soon.

There are a couple of easy ways to tell which code is in the top 20%:

- paying attention to code reviews

- checking the commit history

Take notes, draw diagrams

I discovered that taking notes and drawing diagrams is a very effective way to grok the most complex parts of the code. Call graphs, class diagrams, and dependency graphs all help organize the information and are great reference material in case you need to refresh your memory.

After I joined Amazon, I drew diagrams of a few areas of code I couldn’t understand. They became an instant hit. Even people who had been on the team for much longer than me wanted a copy.

Debug code

Reading a new codebase is like reading a book in a language you barely know. You can do it, but it is excruciating.

For me, one of the best ways to overcome this is to step through the code with the debugger. Initially, I have no idea what I am looking at. But if I follow the same code path a few times, I begin to recognize code I have already seen, and soon, everything starts to fall into place.

To get the most out of my debugging sessions, I do two things:

- I continuously inspect the state – the stack trace, parameters, and local and class variables

- I take notes and draw diagrams

Using the debugger to learn the code base is slower and narrower than reading the code. But it is also much deeper. In fact, when debugging, I often realize that the understanding I gained from reading the code was incomplete or sometimes even incorrect.

Read documentation

Reading documentation can help accelerate your onboarding. It could be especially useful when it comes to the high-level architecture and concepts that are hard to deduce from code.

However, you should take documentation with a grain of salt. It is often sparse and outdated. But this could be good news for you. Updating the documentation as part of your ramp-up could be a great contribution to your new team.

Join on-call rotation

Joining the on-call rotation to accelerate team onboarding might sound extreme but I did it on my first team at Facebook. I did it because I was concerned that my ramp-up was slow, so I decided to push myself. I learned more about our services this week than in weeks before. After my shift ended, I knew what services our team owned, their dependencies and where to find their code. Alerts immediately pointed me to the hot code paths, and troubleshooting issues forced me to dig into the code.