In the previous post, I reviewed the most common data structures and reflected on how often I have used them as a software engineer over the past twenty or so years. In this post, I will do the same for the best-known algorithms.

Searching

Searching for an item in a collection is one of the most common operations every developer faces daily. It can be done by writing a basic loop or using a built-in function like indexOf in Java or First in C#

If elements in the collections are sorted, it is possible to use Binary Search to find an item much faster. Binary search is a conceptually simple algorithm that is notoriously tricky to implement. As noted by Jon Bentley in the Programming Pearls book: “While the first binary search was published in 1946, the first binary search that works correctly for all values of n did not appear until 1962.” Ironically, the Binary Search implementation Bentley included in his book also had a bug – an overflow error. The same error was present in the Java library implementation for nine years before it was corrected in 2006. I mention this to warn you: please refrain from implementing binary search. All mainstream languages have binary search either as a method of array type or as part of the library, and it is easier and faster to use these implementations.

Fun fact: even though I know I should never try implementing binary search on the job, I had to code it in a few of my coding interviews. In one of them, the interviewer was intrigued by my midpoint computation. I got “additional points” for explaining the overflow error and telling them how long it took to spot and fix it in the Java library.

Sorting

Sorting is another extremely common operation. While it is interesting to implement different sorting algorithms as an exercise, almost no developer should be expected or tempted to implement sorting as part of their job. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when language libraries already contain excellent implementations.

Sometimes, it is better to use a data structure that stores items in sorted order instead of sorting them after the fact.

Bitwise operations

Even though the level of abstraction software developers work at has increased and bitwise operations have become rarer, I still deal with them frequently. What I do, however, is no longer the Hacker’s Delight level of hackery. Rather, it is as simple as setting a bit or checking if a given bit (a flag) is set. Software developers working closer to the metal or on networking protocols use bitwise operations all the time.

Recursion

Mandatory joke about recursion: To understand recursion, you must first understand recursion

I used recursive algorithms multiple times on every job I’ve had. Recursion allows solving certain classes of problems elegantly and concisely. It is also a common topic asked in coding interviews.

Backtracking

The backtracking algorithm recursively searches the solution space by incrementally building a candidate solution. A classic example could be a Sudoku solver, which tries to populate an empty cell with a valid digit and then fills other cells in the same manner. If the chosen digit didn’t lead to a solution, the solver would try the next valid digit and continue until a solution is found or all possibilities are exhausted.

So far, I haven’t used backtracking at my job but I used it to solve some programming puzzles. I found that backtracking can become impractical quickly due to a combinatorial explosion.

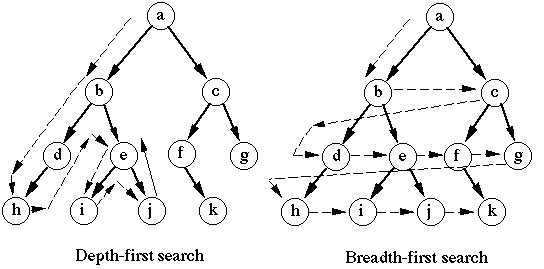

Depth-First Search

Depth-First Search (DFS) is an algorithm for traversing trees and graphs. Because I frequently work with trees, I have used DFS (the recursive version) often, and I have never had to implement the non-recursive version.

DFS is a good bet for interview questions that involve trees.

Breadth-First Search

Breadth-First Search (BFS) is another very popular algorithm for traversing graphs. It has many applications but is probably best known for finding the shortest path between two nodes in a graph.

I have used BFS only sporadically to solve problems at work. DFS was usually a simpler or better choice. BFS is, however, an essential tool for Advent of Code puzzles – each year, BFS is sufficient to solve at least a few puzzles. BFS is also a very common algorithm for coding interviews.

Memoization

Memoization is a fancy word for caching. More precisely, the result of a function call is cached on the first invocation, and the cached result is returned for the subsequent calls with the same arguments. Memoization only works for functions that return the same result for the same arguments (a.k.a. pure functions). This technique is widely popular as it can considerably boost the performance of expensive functions (at the expense of memory).

Dynamic programming

I have to admit that groking the bottom-up approach to dynamic programming took me a while. Even now, I occasionally encounter problems for which I struggle with defining sub-problems correctly. Fortunately, there is also the top-down approach which is much more intuitive. It is a combination of a recursive algorithm and memoization. The solutions to sub-problems are cached after computing them for the first time to avoid re-computing them if they are needed again.

I have used the top-down approach a handful of times in my career, but I have never used the bottom-up approach for work-related projects.

Advanced algorithms

There are many advanced algorithms, like graph coloring, Dijkstra, or Minimum spanning trees, that I have never used at work. I implemented some of them as an exercise, but I don’t work on problems that require using these algorithms.

Image: AlwaysAngry, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons