For the past several months I have been working on the SignalR C++ Client. The first, alpha 1 version has just shipped on NuGet and because there isn’t any real documentation for it at the moment I decided to write a blog post showing how to get started with it.

The SignalR C++ Client NuGet package contains Win32 and x64 bits for native desktop applications and is meant to be used with Visual Studio 2013.

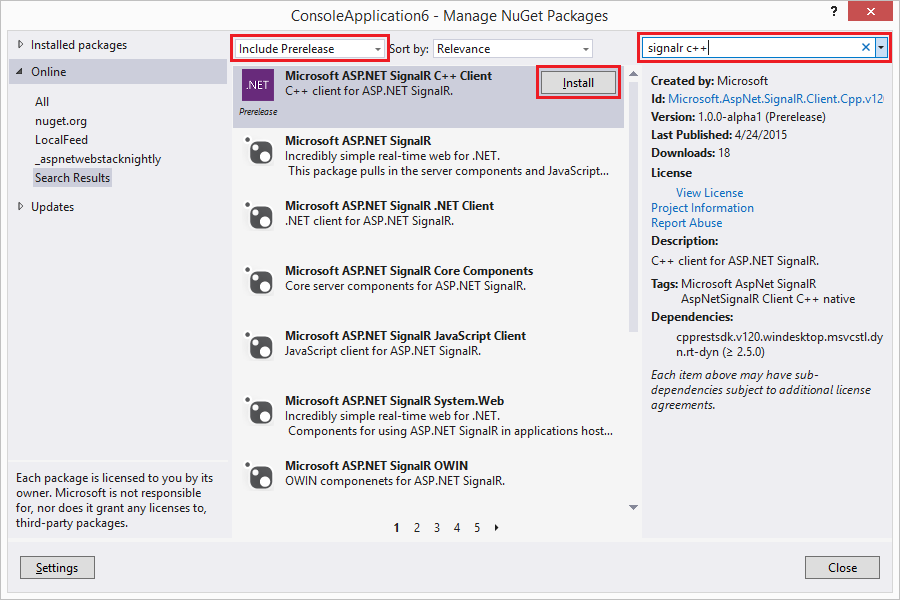

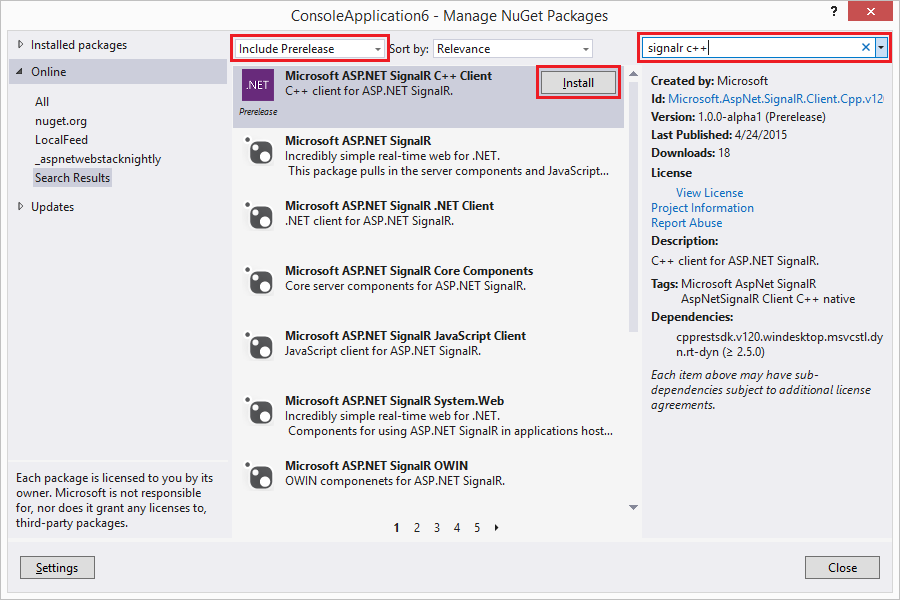

Since the SignalR C++ Client ships on NuGet adding it to a project is easy. After creating a C++ project (e.g. a console application) right click on the project node in the solution explorer and select the “Manage NuGet Packages” option. In the Manage NuGet Package window make sure to include prelease packages in your search by selecting “Include Prerelease” in the dropdown and enter “SignalR C++” in the search window. Finally click the “Install” button next to the Microsoft ASP.Net SignalR C++ Client package which will install the SignalR C++ Client (and its dependency – C++ Rest SDK) into your project.

You can also install the package from the Package Manager Console – just open the package manager console (Tools → NuGet Package Manager → Package Manager Console) and type:

Install-Package Microsoft.AspNet.SignalR.Client.Cpp.v120.WinDesktop –Pre

The SignalR C++ Client relies heavily on asynchronous facilities provided by the C++ Rest SDK (codename Casablanca) which in turn extensively uses lambda functions introduced in C++ 11. Understanding both – asynchronous programming and lambda functions is crucial to being able to use the SignalR C++ Client effectively. I started a blog mini-series on asynchronous programming in C++ which I would recommend to read if you are not familiar with these concepts.

The SignalR C++ Client supports both programming models available in SignalR – Persistent Connections and Hubs. Persistent Connections is just a simple way of exchanging data between the server and the client while Hubs enable RPC-like programming where it is possible to invoke a method on the server from the client and vice versa. In this post I will show how to use the SignalR C++ Client to handle both – Persistent Connections and Hubs.

Before we can move to the client code we need to set up a server. Our server will have two endpoints – one for persistent connections and one for hubs. To make it easy we will use the chat server from the SignalR tutorial as a starting point and we will add a persistent connection endpoint to it. Just follow the steps in the tutorial to create the server. (Alternatively you can get the code from ths SignalR C++ Client GitHub repo – just clone the repo and open the samples_VS2013.sln file with Visual Studio 2013). Note that if you follow the steps you will end up installing the latest stable available NuGet packages into your project instead of the version used in the tutorial and therefore you need to update the index.html file to use the version of the jquery.signalR-x.x.x.min.js that was installed into your project instead of the one used in the tutorial – i.e. if you installed version 2.2.0 of SignalR you will need to change

<script src="Scripts/jquery.signalR-2.0.3.min.js"></script>

to

<script src="Scripts/jquery.signalR-2.2.0.min.js"></script>

You should also set up index.html as the start page by right-clicking on this file in the Solution Explorer and selecting “Set As Start Page”. After you complete all these steps you should be able to run the server (just press Ctrl+F5) and send and receive messages from the browser window that opens.

Now we need to add a Persistent Connection endpoint to our server. It’s quite easy – we just need to add the following class to the project:

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Microsoft.AspNet.SignalR;

namespace SignalRServer

{

public class EchoConnection : PersistentConnection

{

protected override Task OnConnected(IRequest request,

string connectionId)

{

return Connection.Send(connectionId, "Welcome!");

}

protected override Task OnReceived(IRequest request,

string connectionId, string data)

{

return Connection.Broadcast(data);

}

}

}

and configure the server to treat requests sent to the /echo path as SignalR persistent connection requests which should be handled by the EchoConnection class. Adding the following line to the Configuration method in the Startup class will do the trick:

app.MapSignalR<EchoConnection>("/echo");

Our server should be now ready to use so we can now start playing with the client.

Using Persistent Connections

Our EchoConnection sends the "Welcome!" string to the client when it connects and then broadcasts messages it receives from the client to all connected clients. On the client side, after the client connects successfully, we will wait for the user to enter a string which will be sent to the server. We also print any message the client receives from the server. To be notified about messages we need to register a callback which will be invoked for whenever a message is received. Finally, if the user types “:q” (this is the command you want to remember when you try to git commit on a new box but forgot to configure the text editor git should use) the client will close the connection and exit. The code that does all of it is shown below (again, you can get the code from the SignalR-Client-Cpp repo – it is in the PersistentConnectionSample.cpp file)

void send_message(signalr::connection &connection,

const utility::string_t& message)

{

connection.send(message)

// fire and forget but we need to observe exceptions

.then([](pplx::task<void> send_task)

{

try

{

send_task.get();

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

ucout << U("Error while sending data: ") << e.what();

}

});

}

int main()

{

signalr::connection connection{ U("http://localhost:34281/echo") };

connection.set_message_received([](const utility::string_t& m)

{

ucout << U("Message received:") << m

<< std::endl << U("Enter message: ");

});

connection.start()

// fine to capture by reference - we are blocking

// so it is guaranteed to be valid

.then([&connection]()

{

for (;;)

{

utility::string_t message;

std::getline(ucin, message);

if (message == U(":q"))

{

break;

}

send_message(connection, message);

}

return connection.stop();

})

.then([](pplx::task<void> stop_task)

{

try

{

stop_task.get();

ucout << U("connection stopped successfully") << std::endl;

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

ucout << U("exception when starting or closing connection: ")

<< e.what() << std::endl;

}

}).get();

return 0;

}

You may want to try more than one instance of the client to see that all clients receive messages broadcast by the server.

The code is intuitively simple but there are some interesting nuances so let’s take a closer look at it. In the main function, as explained above, we create a connection and we use the set_message_received function to set a handler that will be called whenever we receive a message from the server. Then we start the connection using the connection.start() function. If the connection started successfully we run a loop that reads messages from the console. Note that we know that connection started successfully because if connection.start() threw an exception this continuation would not run at all because it is a value based continuation (you can find more on how exceptions in C++ async work in my blog post on this very subject). Whenever a user enters a message we send the message to the server using the connection.send() function. Sending messages happens in the fire-and-forget manner but we still need to handle exceptions to prevent from crashes caused by unobserved exceptions. When the user enters “:q” we break the loop and move on to the next continuation which stops the connection. This continuation is interesting because it actually can be invoked in one more case. Note that this is a task based continuation so it will be invoked always – even if a previous task threw. As a result this continuation is also an exception handler for the task that starts the connection. Moving back to stopping the connection – stopping a connection can potentially throw so again we need to handle the exception to prevent from crashes.

There are two more important things. One is that tasks are executed asynchronously so we have to block the main thread to prevent the program from exiting and terminating all the threads (see another blog post of mine for more details). In our case we can just use the task::get() function – it is sufficient, simple and works. The second important thing is related to how we capture the connection variable in one of the continuations. We capture it by reference. We can do that because we block the main thread and therefore we ensure that the reference we captured will be always valid. In general case however capturing local variables by reference will lead to undefined behavior and crashes if the function that started a task exited before the task completes (or is even started) since the variable will go out of scope and the captured reference will no longer be valid. Blocking a thread to wait for the task works but usually is not the best way to solve the problem. If you cannot ensure that the reference will be valid when a task runs you should consider capturing variables by value or, if it is not possible (like in the case of the connection and hub_connection instances) capture a std::shared_ptr (or std::weak_ptr). Regardless of how you capture your variables (maybe except for primitive values captured by value) you need to make sure you work with them in a thread safe way because you never know what thread a task is going to run on.

Using Hubs

The sample for hub connections shows how to connect and communicate with the SignalR sample chat server. The code looks like this (you can also find it on GitHub in the HubConnectionSample.cpp):

void send_message(signalr::hub_proxy proxy, const utility::string_t& name,

const utility::string_t& message)

{

web::json::value args{};

args[0] = web::json::value::string(name);

args[1] = web::json::value(message);

proxy.invoke<void>(U("send"), args)

// fire and forget but we need to observe exceptions

.then([](pplx::task<void> invoke_task)

{

try

{

invoke_task.get();

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

ucout << U("Error while sending data: ") << e.what();

}

});

}

void chat(const utility::string_t& name)

{

signalr::hub_connection connection{U("http://localhost:34281")};

auto proxy = connection.create_hub_proxy(U("ChatHub"));

proxy.on(U("broadcastMessage"), [](const web::json::value& m)

{

ucout << std::endl << m.at(0).as_string() << U(" wrote:")

<< m.at(1).as_string() << std::endl << U("Enter your message: ");

});

connection.start()

.then([proxy, name]()

{

ucout << U("Enter your message:");

for (;;)

{

utility::string_t message;

std::getline(ucin, message);

if (message == U(":q"))

{

break;

}

send_message(proxy, name, message);

}

})

// fine to capture by reference - we are blocking

// so it is guaranteed to be valid

.then([&connection]()

{

return connection.stop();

})

.then([](pplx::task<void> stop_task)

{

try

{

stop_task.get();

ucout << U("connection stopped successfully") << std::endl;

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

ucout << U("exception when starting or stopping connection: ")

<< e.what() << std::endl;

}

}).get();

}

Let’s quickly go through the code. First we create a hub_connection instance which we then use to create a ChatHub proxy. Then we use the on function to set up a handler which will be invoked each time the server invokes the broadcastMessage client method. Note that the callback takes a json::value as a parameter which is an array containing parameters for the client method. If you ever used the SignalR .NET client then you probably notice it is different from what you are used to. The SignalR .NET Client does not expose JSON directly but uses reflection to convert the JSON array to typed values which are then passed to the On method as parameters. Since there isn’t reach reflection in C++ it is the responsibility of the user to interpret the parameters the SignalR C++ Client passes to the lambda in the on function. Once the hub proxy is set up we can start the connection and wait for the user to enter a message which we will then send to the server by invoking the server side send hub method. Server side hub methods are invoked with the hub_proxy::invoke function. This function has two flavors. One for methods that don’t return values: hub_proxy::invoke<void>(...), and one used to invoke non-void hub methods: hub_proxy::invoke<json::value>(...). If a server side hub method returns a value it will be returned to the user as a json:value and, again, it is up to the user to make sense out of it. There are also convenience overloads of hub_proxy::invoke function you can use to invoke a parameterless hub method which don’t take the arguments parameter. They will save you a couple lines of code required to create an empty JSON array.

Long running server side methods can notify the client about their progress. If the client wants to receive these notifications it can provide a callback that should be invoked each time a progress message is received. The callback is passed as the last parameter of the hub_proxy::invoke functions and defaults to a lambda expression with an empty body. The sample chat server does not have any method sending progress messages but if you are interested you can check SignalR end to end tests that tests this scenario.

That’s mostly it. The remaining code is just closing the connection and handling exceptions is done the same way as for Persistent Connection.

One important thing worth noting is how we capture the hub_proxy instance in the lambda – we do it by value. hub_proxy type has semantics of std::shared_ptr where all copies point to a single implementation instance which won’t be deleted as long as there is at least one instance that has a reference to it. As a result if you capture a hub_proxy instance by value in a lambda it will be valid even if the original variable is not around anymore. (Not that this matters in this particular example since we are blocking the thread anyways so even if we captured the hub_proxy instance by reference everything would work since the original variable does not go out of scope until the connection is closed).

Doing the right things

There are a few things you need to be aware of when working with the SignalR C++ client.

Prepare the connection before starting

SignalR C++ Client uses callbacks to communicate with the user’s code. However you can only set these callbacks when the connection is in the disconnected state. Otherwise an exception will be thrown. Similarly, when using hubs you have to create hub proxies before you start the connection.

Process messages fast or asynchronously

The callbacks invoked when a message is received (connection::set_message_received, hub_proxy::on) are invoked synchronously from the thread that receives messages. This is to ensure that the callbacks are invoked in the same order as the order the messages were received. The drawback is that the new messages won’t be received until the callback completes processing the current message. Therefore you need to process messages as quickly as possible or, if you don’t care about order, process messages asynchronously.

Handle exceptions

Any kind of network communication is susceptible to errors. Intermittent connection losses and timeouts may and will happen and they will result in exceptions. These exceptions have to be handled otherwise your app will crash due to an unobserved exception. To make exception handling easier the SignalR C++ Client follows a pattern where functions returning pplx::task<T> will not throw exceptions in case of errors but will instead return a faulted task. This saves the user from having to have an exception handler in addition to handling exceptions in a task based continuation. (You can read more about handling exceptions when using tasks here.

Capture connection and hub_proxy instances correctly

Copy constructors and copy assignment operators of the connection and hub_connection classes are intentionally deleted. This was done to prevent from capturing connection and hub_connection instances by value in lambda expressions (I also don’t think there is a clear answer as to what the operation of copying a connection should do). The issue with capturing connection and hub_connection instances by value is that because these classes use a std::shared_ptr pointing to the actual implementation it is possible to create a cycle which would prevent from destroying the connection instance (i.e. the destructor wouldn’t run). The cycle would result not only in a memory leak but would also keep the connection running after the variable went out of scope if the connection was not explicitly stopped – the destructor is responsible for stopping connections that were not stopped explicitly. The cycle would be created if a connection/hub_connection instance was captured by value in callbacks that are passed back to and stored in the connection or hub_connection instances i.e. callbacks passed to connection::set_message_received, set_reconnecting, set_reconnected, set_disconnected functions on both connection and hub_connection.

While deleting copy constructors and copy assignment operators on connection and hub_connection classes makes it more difficult to create a cycle it does not make it impossible – you could still inadvertently create a cycle if you capture a std::shared_ptr<connection> or std::shared_ptr<hub_connection> by value. So, what to do? The safest way is to create a weak pointer (std::weak_ptr) to the connection and capture this pointer. Then in the callback you will need call std::weak_ptr::lock() function to obtain a shared pointer to the connection. You need to check the return value of the std::weak_ptr::lock() function – it will return the nullptr if the instance it points to was destroyed (in which case you probably will want just to exit the callback). You could also try capturing the connection instance by reference by you will have to ensure that the reference is always valid when the callback is executed which sometimes might be hard to do.

Note that capturing hub_proxy instances by value is fine. Hub_proxy is linked back to the connection using a weak pointer so capturing hub_proxy instances by value won’t create cycles. If you, however, try invoking a function on a hub_proxy instance that outlived its connection an exception will be thrown.

Stop connection explicitly

While the connection is being stopped when the instance goes out of scope it is recommended to explicitly stop connections. Stopping the connection explicitly has a few advantages:

- Throwing an exception from the destructor in C++ results in undefined behavior. As a result the connection class destructor (or to be more accurate the connection_impl dtor) catches and swallows all the exceptions. When stopping connections explicitly all the exceptions are passed back to the user (in form of a faulted task) giving the user a chance to handle them the way they see it fit

- Stop is an asynchronous operation but the destructor isn’t. Therefore when the connection is running when the destructor is called the destructor blocks and waits until the stop operation completes. Since the destructor runs in the current thread you might experience “unexpected” delays – “unexpected” because the delay will happen even though you didn’t invoke any function explicitly. Rather the destructor is just called automatically for you when the variable leaves the scope (or when you call delete on dynamically allocated instances). These delays could be especially annoying if the current thread the destructor is running in happens to be the UI thread

- Relying on the destructor stopping the connection may result in the connection not being stopped at all. Internally the connection is using

std::shared_ptr pointing to the actual implementation which will be destroyed only when no one is referencing it. In case of a bug where the connection implementation instance stores a callback that captures its connection instance a cycle is created and the reference count will never reach 0. In this situation the destructor will never be called which means that not only would memory be leaked but also that the connection would never be stopped

Logging

The SignalR C++ Client is able to log its activities. You can control what activities are being logged and how they are logged. To control what’s being logged pass a trace_level to the connection or hub_connection constructor. The default setting is to log all activities. To control how the activities are logged you need to create a class derived from the log_writer class and pass a std::shared_ptr pointing to your writer in the when creating a connection/hub_connection instance. Your implementation has to ensure that logging is thread safe as the SignalR C++ Client does not synchronize logging in any way. If you don’t provide you own log_writer the SignalR C++ Client will use the default implementation that uses the OutputDebugString function to log entries. This is especially useful when debugging the client with Visual Studio since entries logged this way will appear in the Visual Studio Output window.

Limitations

While the SignalR C++ Client is fully functional it contains a couple of limitations. Currently the client supports only the webSockets transport. It also does not support detecting stale connections using the heartbeat mechanism. (The way heartbeat works in other clients is that the server sends keep alive messages every few seconds and if the client misses a few of these keep alive messages it will consider the connection to be stale/dead and will try restarting the connection. The SignalR C++ Client currently ignores keep alive messages). Finally, the SignalR C++ Client does not support sending or receiving State information.

Future

This is only an alpha 1 release. I expect there will be some bugs that have not been caught so far and fixing them should be a priority. Another interesting exercise is to try to make the SignalR C++ Client work on other platforms – specifically on Linux and Mac OS. It should be possible because the SignalR C++ Client is built on top of C++ REST SDK which is cross platform. Finally – depending on the feedback – adding new transports (at least the longPolling transport) may be something worth looking at.